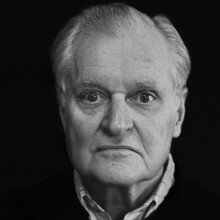

John Ashbery is recognized as one of the greatest twentieth-century American poets. He has won nearly every major American award for poetry, including the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Yale Younger Poets Prize, the Bollingen Prize, the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Griffin International Award, and a MacArthur “Genius” Grant.

Ashbery's poetry challenges its readers to discard all presumptions about the aims, themes, and stylistic scaffolding of verse in favor of a literature that reflects upon the limits of language and the volatility of consciousness. In the New Criterion, William Logan noted: "Few poets have so cleverly manipulated, or just plain tortured, our soiled desire for meaning. [Ashbery] reminds us that most poets who give us meaning don't know what they're talking about." The New York Times Book Review essayist Stephen Koch characterized Ashbery's voice as "a hushed, simultaneously incomprehensible and intelligent whisper with a weird pulsating rhythm that fluctuates like a wave between peaks of sharp clarity and watery droughts of obscurity and languor."

Ashbery’s first book, Some Trees (1956) won the Yale Younger Poets Prize. The competition was judged by W.H. Auden, who famously confessed later that he hadn’t understood a word of the winning manuscript. Ashbery published a spate of successful and influential collections in the 1960s and ‘70s, including The Tennis Court Oath (1962), The Double Dream of Spring (1970), Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975) and Houseboat Days (1977). Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, considered by many to be Ashbery’s masterpiece, won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award, an unprecedented triple-crown in the literary world. Essentially a meditation on Francesco Parmigianino’s painting "Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror," the narrative poem showcases the influence of visual art on Ashbery’s style, as well as introducing one of his major subjects: the nature of the creative act, particularly as it applies to the writing of poetry. This is also, as Peter Stitt noted, a major theme of Houseboat Days, a volume acclaimed by Marjorie Perloff in Washington Post Book World as "the most exciting, most original book of poems to have appeared in the 1970s." Stitt maintained in theGeorgia Review that "Ashbery has come to write, in the poet's most implicitly ironic gesture, almost exclusively about his own poems, the ones he is writing as he writes about them." Roger Shattuck made a similar point in the New York Review of Books:"Nearly every poem in Houseboat Days shows that Ashbery's phenomenological eye fixes itself not so much on ordinary living and doing as on the specific act of composing a poem…Thus every poem becomes an ars poetica of its own condition."

Critics have noted how Ashbery's verse has taken shape under the influence of abstract expressionism, a movement in modern painting stressing nonrepresentational methods of picturing reality. "Modern art was the first and most powerful influence on Ashbery," Helen McNeil declared in the Times Literary Supplement. "When he began to write in the 1950s, American poetry was constrained and formal while American abstract-expressionist art was vigorously taking over the heroic responsibilities of the European avant garde." True to this influence, Ashbery's poems, according to Fred Moramarco in the Journal of Modern Literature, are a "verbal canvas" upon which the poet freely applies the techniques of expressionism.

Ashbery's experience as an art critic in France during the 1950s and ‘60s, and in New York for magazines like New York and the Partisan Review strengthened his ties to abstract expressionism. But Ashbery's poetry, as critics have observed, has evolved under a variety of influences besides modern art, becoming in the end the expression of a voice unmistakably his own. Ashbery’s influences include the Romantic tradition in American poetry that progressed from Whitman to Wallace Stevens, the so-called "New York School of Poets" featuring contemporaries such as Frank O'Hara and Kenneth Koch, and the French surrealist writers with whom Ashbery has dealt in his work as a critic and translator.

[. . .]

For more information on John Ashbery (including an extensive bibliography), visit his page at the Poetry Foundation.