A musical note of our era

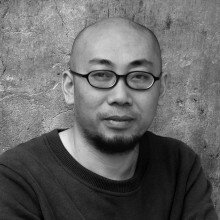

For Zheng Xiaoqiong, as a prominent, award-winning poet and former migrant worker herself, writing about migrant workers’ experiences is an ethical question inseparable from aesthetic concerns and poetic forms. Zheng explores the possibilities of articulating the experiences of migrant workers through various poetic devices, including manipulation of language and experimentation with line- arrangement on the page. Critics in China have offered insightful readings of her poems. Zhang Qinghau, in his provocative essay ‘Who Touches the Iron of the Age: On Zheng Xiaoqiong’s Poetry’, notes the power of Zheng’s unique diction and imagery, which not only reveal the marginalized lives in the lower strata of society, but also capture the characteristics of the contemporary era through a “new aesthetics of iron”:

While Zhang focuses on the aesthetic significance of Zheng’s poetry, Gong Haomin points out its ecological concerns in his essay ‘Toward a New Leftist Ecocriticism in Postsocialist China: Reading the ‘Poetry of Migrant Workers’ as Ecopoetry’. Gong discusses the characteristics of migrant workers’ poetry, which show that the poets’ sense of their identity shapes the ways they “conceive their relationship with nature”. Apart from “bearing witness to the pollution and the destruction of nature in the unchecked process of industrialization and urbanization, these poets, disoriented in an urban environment, usually see their own experience in parallel with a nature disturbed by human interventions. For instance, plants uprooted from the earth is an image that appears repeatedly” (148).

Though both Zhang and Gong’s insights shed light on some significant aspects of Zheng’s poetry they overlook other, related, issues that Zheng confronts, such as: industrial diseases, disintegration of migrant workers’ families, and the ‘hollowing’ of villages, as well as migrant workers’ resistance to subjugation and exploitation. My reading of Zheng’s poems seeks to foreground their poetic agency in confronting the impact of urbanization and economic globalization, and in giving voice to migrant workers in China. But given the range of thematic concerns and poetic forms, Zheng’s work refuses the label of “literature of migrant labor”. In fact, to quote her own words, the poems by Zheng Xiaoqiong could be better understood as a “musical note of our era” (Female Migrant Workers 180). Yet, for Zheng, this musical note of the times must include the migrant workers’ voice and experience. In poems such as ‘Migrant Labor, Words of Vicissitudes’, the broken lines and disrupted syntax mirror the dislocation, uncertainty, and fragmented lives of migrant workers. As the speaker states by the end of the poem, while seeking to redeem and reclaim migrant workers’ lives, she simply “can no longer calmly, quietly, silently write poems. . .” For words like ‘migrant labor’ “no longer inhabit a poetic landscape” (‘Migrant Labor’ Pedestrian Overpass 74).

In searching to find a suitable language for portraying migrant workers’ experience and its socio-historical context, Zheng has developed a poetics that characterizes the ways in which the workers’ physical and psychological conditions are shaped by their working and living environments, which are produced by both local and global forces. Entangled social, cultural, and physical environments play an active role in giving rise to the phenomenon of migrant workers, and in altering their physical, psychological, and social statuses. The concept of ‘trans-corporeality’ proposed by the feminist ecocritic Stacy Alaimo offers a theoretical framework for understanding the multiple interrelations and effects underlying Zheng’s poems. Alaimo defines trans-corporeality as “the time-space where human corporeality, in all its material fleshiness, is inseparable from ‘nature’ or ‘environment’.” She contends that ‘Trans-corporeality’, “the movement across human corporeality and nonhuman nature [that] necessitates rich, complex modes of analysis that travel through the entangled territories of material and discursive, natural and cultural, biological and textual” (‘Trans-Corporeal Feminisms’ 238). Such movement across the body of the migrant worker and its environments in intertwined, heterogeneous networks characterizes Zheng’s portrayal of migrant workers’ situations.

Her poems such as ‘An Iron Nail’, ‘Nails’, and ‘Lungs’ suggest that the materiality of an industrial environment has penetrated the workers’ bodies and minds, shaping their sense of self as well as the prospects of their future. In ‘An Iron Nail’, Zheng employs an iron nail as an analogy for the life of a female migrant worker. Although the female migrant worker, who has turned into an iron nail, does not complain, the poem itself is a powerful protest against the injustice of dehumanizing exploitation through layered meanings embedded in the images. The barren, desolate, and hopeless life of the female migrant worker as a nail fixed on the wall serving a diminutive, subordinate, yet useful function for her master’s daily living contrasts his well-to-do yet banal commonplace life, which depends on the nail for a particular purpose. The critical distance created by the speaker’s ironic tone also exposes the fact that limited choices in life have conditioned the female migrant worker’s outlook, symbolically crippling her for life. Thus the dominant image of the iron nail points to systemic conditions that confine and devalue the migrant workers’ existence.

Zheng often situates the migrant workers’ condition in a larger context of industrialization and globalization. The changing landscape, including urbanization and environmental destruction, seen through the eyes of a migrant worker in ‘The Lychee Grove’, at once reflects and critiques the complex impact of industrialization equated with prosperity, progress, and Westernization. The river that “still keeps / The slow pace and sadness of the past era,” is likened to “a sick person” whose sickness is marked by industrial pollution—”It’s greasy, swarthy, stagnate with the stench of industrial wastes” (Poems Scattered 35). Like migrant workers who suffer from industrial diseases, the river is “sick” because of industrial pollution. Their plight is part of the social, cultural, and environmental transformations taking place. While the scenes of urbanization and industrialization in this poem are local, they are connected to economic globalization in other poems. Using nails as an extended metaphor in the poem ‘Nails’, Zheng indicates the dehumanization of workers, who have become parts of machines for production and profit. Yet, unlike machines, countless workers suffer from endless fatigue, industrial maladies, violation of their rights, homesickness, and a sense of being trapped in a meaningless, hopeless situation as cheap labor.

Thus, the ‘trans-corporeality’ in this piece and in Zheng’s other poems about migrant workers entails more than “the material interconnections of human corporeality with the more-than-human world,” which Alaimo’s concept of ‘trans-corporeality’ emphasizes (‘Trans-Corporeal Feminisms’ 238). While ‘Nails’ demonstrates the inseparable connections between “environmental health, environmental justice, the traffic in toxins”—connections which the concept of trans-corporeality helps highlight (‘Trans-Corporeal Feminisms’ 239), the poem also reveals the psychological and emotional dimensions of migrant workers’ living and working conditions, which are also shaped by economic globalization. The implied connections between local and global, between working environments and migrant workers’ work-related illnesses become more explicit in poems such as ‘The Age of Industry’ collected in Poems Scattered on the Machine. The interlaced references and images in the poem suggest intertwined connections between the female migrant worker’s fatigue, sickness, and the products sold on the U.S. market, and between economic globalization and environmental destruction in China, especially in the countryside and the so-called economic development zones.

As Alaimo eloquently argues, matters of environmental concern are always “simultaneously local and global, personal and political, practical and philosophical. Although trans-corporeality as the transit between body and environment is exceedingly local, tracing a toxic substance from production to consumption often reveals global networks of social injustice, lax regulations, and environmental degradation” (Bodily Natures 15). By following the movement of migrant labor from an inland village to a costal factory, and the movement of the factory’s products to the stores in the U.S., and by juxtaposing the images of the coughing migrant worker in the factory with the greasy sobbing water and felled lychee trees in the development zone, Zheng depicts precisely the kind of ‘trans-corporeality’ that exposes global networks of social injustice and environmental degradation. Yet the global North remains safely distant from the immediate impact of such social injustice and environmental destruction.

Moreover, Zheng’s poems, for example ‘Lungs’, highlight the fact that the impact of toxic environments on migrant workers ripples beyond individuals and production sites to the countryside. In fact, the migrant worker’s ‘lungs’ in the poem can be understood as “the proletarian lung within the networks of nature/culture, which are “simultaneously real, like nature, narrated, like discourse, and collective, like society” (Latour qtd. in Alaimo Bodily Natures, 28). Effectively deploying the image of diseased ‘lungs’ as an extended metaphor in the poem, Zheng stretches the complex socio-economic ecological web even wider, and the impact of environmental injustice against migrant workers uncontainable to factories. Zheng tactfully links the penetration of industrial dusts into the migrant worker’s lungs to the disintegration of migrant workers’ families and the wreckage of plunder of natural resources in the countryside. In so doing, she situates migrant workers’ vocational diseases and the collapse of their families in the context of larger social and environmental problems resulting from interrelated economic globalization, local economic development and industrialization, which have led to the displacement of millions of migrant workers, like a father dying of industrial disease in a factory far away from his family.

As she further investigates the predicament of migrant workers, Zheng links their labor and work environment to globalization, and suggests that migrant labor in China reflects an unequal relationship between a mutually constituted global North and global South. In her poems The Age of Industry’, ‘Through the Industrial District’, and ‘Midnight, Rain’ Zheng calls critical attention to the ethical, social, and environmental issues underlying an unequal yet interconnected relationship between the global South and global North. She juxtaposes the transnational networks of industry and commerce with a variety of local dialects in a factory to highlight the connection between migrant labor in China and economic globalization, which has brought about a new era of industrialization in China and an emergent ‘global South’ within the country. The ironic tone of the speaker underlines the power of transnational capital of the global North, whose transformative impact on people’s lives and the environment in China is implied in the scene of a factory, which is contextualized in networks of the global market.

Zheng’s poems about migrant workers accomplish more than bearing witness to social and environmental injustice, and more than reclaiming disappeared, marginalized lives at the bottom of society. Even though Zheng often compares the migrant worker to ‘iron’ that is mute and subject to being cut, slated, melted, hammered, reshaped, and used, she observes the transmutation of matter for inspiration about the transformation of migrant workers’ bodies and spirits in order to resist oppression, and to overcome. Thus, a transformative ‘trans-corporeality’ often takes place in her poems, like in ‘Those to Demand Their Wages on Their Knees’, in which the mute female migrant workers’ bodies enact a courageous protest and resistance:

They flash by like ghosts at train stations

Around machines in the industrial zones and dirty rentals

Their thin figures are like blazes like white paper Like hair like air they have cut with their fingers Iron films plastic . . . they are tired and numb Looking like ghosts they are put into machines Overalls assembly lines they are bright-eyed

Youthful they flash into the floods made up of themselves

The dark waves I can no longer tell them apart

Just as I’m indistinguishable standing among them only skin

Limbs movements blurred features one after another

Those innocent faces are ceaselessly grouped lined up Forming ant colonies bee hives of toy factories they are Smiling standing running bending curling up then each Reduced to a pair of hands thighs

Becoming tightly tightened screws cut into pieces of iron

Pressed into plastic twisted into aluminum threads tailored to cloth

[. . .]

Now they’re kneeling on the ground facing huge bright glass doors and windows

Black-uniformed security guards shiny cars New Year’s greeneries

The golden factory signboard is glittering under the sunlight

They are on their knees at the factory gate holding a piece of cardboard

With clumsy handwritten words “Give Me My Blood & Sweat Pay”

They four are fearless kneeling at the factory gate

(from ‘Female Migrant Workers’ 107-108)

Even though these female migrant workers are dragged away by security guards, their performance of ‘begging’ in public is a powerful gesture of defiance, a rebellious demand for fair treatment, a protest against injustice. In contrast to their diminished status, being reduced to body parts and disciplined into a uniform collective like ‘ant colonies’ and ‘bee hives’, the corporeal agency of the four courageous female workers is particularly unsettling. The trans-corporeal movement between the workers’ bodies and the objects in the ‘contact zone’ of the toy factory enact transformations of the subjugated and abused bodies. Female migrant workers who are becoming iron, plastic, tightened screws, and a uniform collective unexpectedly use their bodies to perform resistance that disrupts the apparently well-organized and disciplined docile behavior of migrant workers.

In sounding “a musical note of our era”, the poems by Zheng Xiaoqiong enact a socially engaged ethical and aesthetic commitment of the poet and her poetry. They compel the reader to expand notions of community and rights for social, ecological, environmental justice beyond national borders, while offering an effective mode of knowing that is at once rewarding and unsettling.

A much longer and somewhat different version of this essay is to be published as a chapter entitled ‘Scenes from the Global South China: Zheng Xiaoqiong’s Poetic Agency,’ included in the anthology Ecocriticism of the Global South, edited by Vidya Sarveswaran, Swarnalatha R., and Scott Slovic, forthcoming from Lexington Books/Rowman & Littlefield.

Works Cited

Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Alaimo, Stacy. “Trans-Corporeal Feminisms and the Ethnical Space of Nature.” In Alaimo and Hekman. 237–64.

Alaimo, Stacy and Susan Hekman, eds. and intro. Material Feminisms. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Bruno, Latour. We Have Never Been Modern. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Gong, Haomin. “Toward a New Leftist Ecocriticism in Postsocialist China: Reading the ‘Poetry of Migrant Workers’ as Ecopoetry.” China and New Left Visions: Political and Cultural Interventions. Ed. Ban Wang & Jie Lu. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2012.139–57.

Zhang, Qinghua. “Who Touches the Iron of the Age: On Zheng Xiaoqiong's Poetry.” Chinese Literature Today. 1.2 (Summer 2010): 31–35.

Zheng, Xiaoqiong. Female Migrant Workers. Guangzhou: Flower City Publishing House, 2012.

——. Pedestrian Overpass. Taiwan, Taibei: Tanshang Publications, Inc., 2009.

——. Poems Scattered on the Machine. Beijing: China Society Publishing House, 2009.

Abstract grunge music image via Shutterstock.