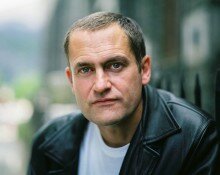

Born in 1961, Ifor ap Glyn is a poet, playwright, historian, producer and current national poet of Wales. He has published four volumes of poetry and has contributed to many anthologies. An active performer, he has taken part on many poetry tours including Cicio’r Ciwcymbars, Dal Clêr, Lliwiau Rhyddid, and Dal Tafod. He is also a member of the Caernarfon team which has twice won the annual poetry knockout competition on BBC Radio Cymru, Talwrn y Beirdd. He has represented Wales twice at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in the USA and has won the Crown at the National Eisteddfod twice, in 1999 and 2013. He was the Children’s Laureate for Wales in 2008-9. His first novel, Tra Bo Dau, was published by Gwasg Carreg Gwalch in 2016. He is based in Caernarfon, north Wales.

Ifor ap Glyn was born and raised in London; the fourth generation of his family to live in the British capital. He spent the summers of his youth with his grandparents in Wales, strengthening his command of his mother tongue and his appreciation of the culture which still flourished in the chapels and Welsh societies of London. Having passed his A Level in Welsh Literature (without any formal tutoring in the language), he applied for, and was given a place to read Welsh at Cardiff University.

To understand ap Glyn’s work, it pays to have an understanding of the Wales that subsequently shaped him. Ap Glyn began his studies in Cardiff at a time when the mettle of the nation was severely tested. In the 1979 referendum, Wales voted four to one against devolution, a huge setback to the nationalist cause. At this time, the Welsh language pop music scene was particularly vibrant, providing a platform for protest which ap Glyn exploited with his band Treiglad Pherffaith – ‘The Perfect Conjugation’ (deliberately written in imperfect conjugation).

Poetry evolved out of his song-writing. An anarchic singer, he turned into a flamboyant performance poet. In the foreword to his first collection, ap Glyn outlined his aims for a “poetry that was written to be performed... poetry for the use of the nation. That’s what’s important”. In so doing, Ap Glyn aligned himself, from the outset, with the old bardic tradition; with singing for the people. His poem ‘Ciwcymbars Wolverhampton’, published in Holl Garthion Pen Cymro Ynghyd (1991), was an early crowd pleaser. This poem takes the fact that human beings are made up of two thirds water, and uses it to posit that the inhabitants of Wolverhampton (whose water is supplied by Wales) be just as ‘Welsh’ as the Welsh themselves.

there are ten million forgotten Welsh ‘others’

Let’s push Offa’s Dyke away eastwards

So we can re-link with our brothers.

It would solve our problems with tourism

‘cos then they’d be living here too.

Powys would reach up to Norfolk

and Gwynedd would finish in Crewe

Playfully pursuing this theory, he went on to conjecture that cucumbers, being ninety percent water, if grown in Wolverhampton, are more Welsh than the people of Wales, ‘yn Gymreicach na’r Cymry i gyd’. Such satirical swipes against received notions of Welsh identity are typical of ap Glyn’s irreverent humour.

To borrow historian Gwyn Alf Williams’ phrase, Welsh poets have also been people’s ‘remembrancers’. We see this dual function clearly in ‘Cymraeg badge’, one of the poems in the collection Terfysg (Conflict) (2013) which won him the crown at the National Eisteddfod in 2013.

Searching in vain

for a badge of permission,

the orange comma of continual discretion

lest anyone be offended.

We pause together, as a nation,

holding our breath for too long ...

make the language a stick of confidence in our hand!

Revolutionary zest

is the only road to success ...

Poetry in Welsh is political; an act of reaffirmation. Yet, writing in Welsh, ap Glyn’s work also needs to address the 80% of the Welsh population whose first and perhaps only language is English - ap Glyn is no stranger to presenting his work with the aid of translation. There is still, however, a common appreciation of the language and its heritage. As his predecessor as national poet of Wales, Gillian Clarke, has noted, Welsh is one of the treasures of Britain: “Like the cathedrals – we may not use them ourselves - but we wouldn’t want to lose them”.

Waliau’n Canu (Singing Walls) (2011) is a deeply personal and political body of work. The angry young poet is still incensed by the casual and unchecked nature of injustices inflicted both upon his own people and others. However, whilst his early performance pieces had a fiery, punk-like quality, the incendiary work in this volume burns with a deeper complexity; napalm poetry. Though still written to be performed, the collection rewards the reader with further nuances and layers of invention.

In the poem ‘Y Tyst’ (‘The Witness’), ap Glyn references the poem ‘Aneurin’ by fellow bard, Iwan Llwyd , in a further meditation upon his own commitment to the poet’s duty.

shoulder to shoulder

And sleeping with light in my eyes,

Like the others

I chose to live this nightmare.

My song burns within me

Dispersing the darkness that I saw

My song is the brand of Cain on my brow

‘He was with them,

but he came back’

‘[T]hem’ refers to the three hundred Welsh warriors who, after a year of feasting, set off to fight foreign invaders at Catraeth (modern day Catterick), then part of the Welsh kingdom of Rheged. Their heroic deaths are the basis of the oldest poem in the Welsh language – the ‘Gododdin’ written by Aneurin in the 6th century. In this, only one person returns from the battle, the poet himself, who is left to sing of their bravery. Aneurin was the original chronicler of his people, a witness of horror who sings on behalf of all. As ap Glyn writes:

At Hillsborough, taking pictures

Not hauling victims from the crush

At Aberfan asking questions

of those that wept

not clawing with my nails in the slurry

At Mametz Wood (iv) writing to mothers

“Your son died quick, on a hero’s mission

Bravely charging an enemy position”

Though I saw him writhing a long while

On death’s barbed wire (…)

But yes, I was there at Catraeth

In every generation’s Catraeth.

My song is a Judas on my lips

I’m forced to live with what I saw

And my inability to change it

I honour the dead with my failure.

I have to live. I am the witness

There is a certain irony in writing about ap Glyn’s work whilst quoting his lines in translation. Ap Glyn himself considers this irony in ‘Cyfieithiadau’, his own translation of ‘Aistriúcháin’ by the Irish poet, Gearóid mac Lochlainn. It concerns a poet’s thoughts upon performing before a bilingual audience, inferring that bilingualism can lead to compromise and dominance of the other language.

of the ear scratching of listeners,

the monolingual ones that say smugly

‘It sounds lovely. I wish I had the Irish.

Don’t you do translations?’

Ap Glyn has translated Irish poems, written two trilingual theatre texts, Branwen and Frongoch, and directed Welsh / Irish co-productions for television. He and mac Lochlainn are of the same mind in viewing language as the codification of a culture; lose a language and you lose more than words; you lose a poet’s ability to sing of and for his people.

Ap Glyn’s language is rich and reflexive, both of itself and of the constantly challenged minority culture within which it is rooted. The poem ‘Ar Ddechrau Tymor Newydd’ (‘At the Start of a New Term’), questions the effect of tourism upon the people of the Llŷn peninsula, an area in which Welsh speakers are very much in the majority:

Ein ffenics pob Gorffennaf

Ai gwegian pan y gwagia

a wnawn? Yr ateb yw na.

Daw gaeaf. Ond nid gwywo

Yn brudd wna bywyd ein bro.

Cyfnod pan atgyfodwn

Yw’r gaea’ ym Morfa, m’wn.

(Do they not make our summer?

Our phoenix each and every July.

Do we ache when they leave?

The answer is no

The winter comes. But our lives

in these heartlands do not die

winter is a time when we arise

again in Morfa).

Ap Glyn’s poetry is a poetry that strives for freedom; both personal and political. It simultaneously entertains and demands action of the people; the act of social conscience. Ifor ap Glyn chooses the path of the witness, and Wales is a better place because he sings for it.

Bibliography

Poetry

Holl Garthion Pen Cymro Ynghyd, Y Lolfa, Talybont, 1991

Golchi Llestri mewn Bar Mitzvah, Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 1998

Cerddi Map yr Underground, Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 2001

Waliau’n Canu, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 2011

In Translation:

English

Oxygen: New Poets from Wales. Eds. Amy Wack and Grahame Davies. Seren Books, Bridgend, 2000

The Bloodaxe Book of Modern Welsh Poetry. Eds. Menna Elfyn and John Rowlands. Bloodaxe, Tarset, 2003

Asturian

Nel pais de la borrina. Ed. Grahame Davies. vtp editorial, Gijón/ Xixón, 2004

Galician

Dorna magazine, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, 2014

In Anthology:

Dal Clêr. Ed. Menna Elfyn. Hughes a’i Fab, Caerdydd, 1993

Bol a Chyfri Banc. Eds. Myrddin ap Dafydd and Iwan Llwyd. Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 1998

Syched am Sycharth, Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 2000

Lliwiau Rhyddid, Bara Caws, Caernarfon, 2001

Novel

Tra Bo Dau, Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 2016

History

Lleisiau’r Rhyfel Mawr. Ed. Lyn Ebenezer. Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, 2008

‘Censorship and the Welsh Language in the First World War’ in Languages and the First World War: Communicating in a Transnational War. Eds. Julian Walker and Christophe Declercq. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2016

Links

ap Glyn’s National Poet profile on Literature Wales

ap Glyn’s appointment as National Poet of Wales in The Guardian

ap Glyn featured in an overview of Welsh language literature in The Guardian

ap Glyn performing at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival 2013

ap Glyn performing at the Caernarfon Festival 2006