Angifi Proctor Dladla was born on 24 November 1950 in Thaka township in Gauteng, formerly the Transvaal. His mother was a domestic worker and his father, initially a teacher, went into industry. After his parents’ divorce in his early childhood, he moved from Irene to Kgabalatsane, to Shoshanguve, visiting his father in KwaDukathole and later, Katlehong. He started writing poetry and plays while still a scholar at St. Chad’s High in Ladysmith, where his plays were performed by fellow students. He has worked as a poet, playwright, poetry editor, school teacher and teacher of creative writing. During the apartheid years Dladla went by the name Muntu wa Bachaki to elude the authorities.

Based in Katlehong on the East Rand for most of his life, he is also an active and path-breaking presence in his community, both locally and on a wider stage. He has founded a number of community organisations, among them the Bachaki Theatre and more recently the Community Life Network, a non-profit cultural organisation supporting community reconstruction and development. He also founded Akudlalwa Communal Theatre, ERTON and Boksburg Progressive Presses and the Femba Writing Project, which initiates and facilitates school and prison newspapers and creative writing.

His first poetry collection, The Girl Who Then Feared to Sleep, was published in 2001, and he has continued to publish poems locally and internationally. This debut received widespread praise from critics, who variously speak of its wide range of styles, voices and themes, its raw power and experimental freshness, and its heartfelt response to a society in which racism, violence and the misuse of power are still endemic. Here is a poet who requires us to look at compelling events and issues from which our first instinct has been to turn away.

In an interview with Dladla, Joan Metelerkamp remarks that his poems contain “the sense of objective observation at the same time as intense personal connection . . . grace and pain co-exist in your work. You manage to observe without being overwhelmed.”

Perhaps most strikingly, Dladla is the master of the concise, surreally tinted but devastating image of the real; who can forget the corpse in the street after necklacing in the poem ‘Impression’ that resembles “human gravy in the sun”? Or the “red / shoe on the railway” that “licks shuddering wounds and / wails like a cheated / coffin” (‘Vacancy’); or the Zionist church baptisms in ‘The Intangible’ whose members take “rhetorical dives and blobs / in the watery realm / in search of a vocal mirage / which becomes an echo / the nearer they advance.”

A convinced Pan-Africanist, he speaks of the influence of a number of sources on his writing, especially the South Africans Es’kia Mphahlele, Arthur Nortje, Mazisi Kunene, Keoropetse Willie Kgositsile and the Zulu-language poet and playwright DBZ Ntuli. He also refers to wider poetic influences from Africa that range from Léopold Sédar Senghor and Okot p’Bitek to the Angolan poet, António Jacinto and ancient Egyptian poetry.

Dladla is a critic of the tendency in the modern world for humans to lose their sense of neighbourliness as a result of the burgeoning of materialism. He believes that the South African ideal of ubuntu (human compassion and fellow-feeling) can be found among inhabitants of countries right across the globe. His views about the role of the poet in society are as clear as the kinds of poetry that appeal to him. In the Metelerkamp interview he notes, “Poetry demands a search for the essence of things . . . Poems are with the people; they must remain there.” In an interview with Michelle McGrane he adds, “To me poetry is the language of the soul, the lingua franca of dreams . . . I am just a matchbox for a person’s inner match to unleash his or her human goodness.”

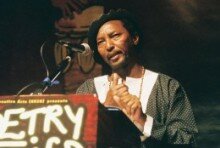

While he is willing to write poems to celebrate special events in the lives of people in his community, he is devastating in his critique of praise poets: “I don’t turn despots into roses and idols. Where are those who glorified Gqozo, Vorster, de Kok, Mobutu? They died with the dying, they disappeared with the disposable.” He is a compelling performer of his work, claiming the stage with an apt sense of theatre. He appears regularly at literary festivals in his own country and abroad.

Dladla’s first foray into editing was the compilation Walala Wasala which included poetry by young writers, prisoners, and members of the Afrika Reads Forum. This title, which translates loosely as ‘You snooze, you lose’, was published in 2004 with a Comunity Publishing Project grant from the Centre for the Book. His latest project is Reaching Out: Poems from Prison, a collection of poems written by inmates he has mentored at the Moderbee Prison.

This issue of Poetry International presents readers with an opportunity to appreciate and enjoy five more examples of Dladla’s craft forthcoming from his next collection, We Are All Rivers, scheduled for publication by Chakida Publishing later this year.

Bibliography

Poetry

The Girl Who Then Feared to Sleep, Deep South, Grahamstown, 2001

We Are All Rivers, Katlehong, Chakida Publishing, 2010

Anthologies

Walala Wasala, Katlehong, Chakida Publishing, 2004

Reaching Out: Poems from Prison, Katlehong, Chakida Publishing, 2010

Links

A poem from the Poetry Africa website

A poem from the City Breath Project

A poem from the Deep South website

Two poems on Botsotso

Seven poems on Litnet

Michelle McGrane interviews Angifi Dladla on Litnet

Critical acclaim for The Girl Who Then Feared to Sleep