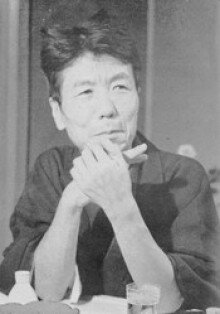

To many Japanese baby-boomers who were born within a decade or so after the end of World War II, Tatsuji Miyoshi was the national poet, and his works appeared in their textbooks almost every school year. Those poems were perfect for classroom teaching: short and handsome, simple yet profound . . . ‘Earth’ is a good example of this – it can be read almost as a free-form haiku, but at the same time there is something Western about it, maybe a hint of the French symbolism or American imagism, which appealed to Japanese people both young and old as the expression of their new sensitivities in free, democratic post-war society.

Those were the days shortly after the poet’s death in 1964 at the age of 64. Nowadays, unfortunately, Tatsuji Miyoshi is not heard about so often, although his collected poems are still in print in several editions and there is even a poetry award commemorating his work. Most contemporary poets seem to consider him a poet of the past, whose poems might have played fine emotional tunes at the time, but lacked social and historical awareness. The fact that, during the war, Miyoshi wrote poems in moral support of the soldiers on the frontlines, if not for the regime itself, must have been partly responsible for such a view.

But if you set aside the ideological judgments and appreciate the landscapes of Tatsuji Miyoshi’s poetry as they are, you will find an extraordinarily wide range of styles and extremely sophisticated techniques, which few poets today can match.

After all, this is a poet who on the one hand translated Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal, and on the other translated and edited an anthology of the Tang Dynasty Chinese poetry, while having composed tanka and haiku throughout his life. Tatsuji Miyoshi is an all-rounder, a rare type of poet in the compartmentalised world of modern Japanese poetry.

The poems presented here show a glimpse of such diversities of his oeuvre: ‘Soft Hail Flutters’ (or ‘The Hail Fell’ in Jeffrey Angles’ translation), ‘Call My Name’ and ‘May the Koto’s Resonance Soar’, all of which are written only in hira-gana (the Japanese phonetic alphabet) without using kanji (Chinese characters), are more music than words, and their melodies echo the ancient Japanese verses such as Man’yo-shu. ‘A Village’ is a shorter example of the prose poem, a favorite form of Tatsuji’s in his late twenties, when he was influenced by Baudelaire. ‘In Praise of the Walnut’ and ‘Verses on a Village Brew’ are written in such a way that those poems can very well be mistaken as the Japanese translations of ancient Chinese poems. Finally, such poems as ‘Family’ and ‘Yet, a Stirring in Me Seems’ (‘But These Feelings Feel Like Spring’ in Jeffrey Angles’ translation) show yet another aspect of the poet as a storyteller.

Behind all of these chameleon-like changes in his poems, however, one can not help but feel the unchanging presence of Tatsuji Miyoshi, more as a person than as a poet. The reader of his work feels as though they had known him personally, and it is his compassion more than anything else that is so touching. Tatsuji Miyoshi is a poet of attachment as opposed to detachment: he reduces the distance between himself and his object, whether it be a human being or nature, until they become one. His songs are born in that moment of togetherness. And yet, “being a poet”, as he wrote in ‘The Shore of the Sky’, he is also a traveller at heart: he moves on, trying to see beyond, “blinking it eyes at the scent of the tides, chasing after clouds that fly away” (from ‘The Lamb’). Tatsuji Miyoshi travelled rather hastily through the most violent and tragic period in the Japanese history. But he has left behind him the songs which are to stay with us for a long time.

Note: Jeffrey Angles and Takako Lento have both translated Tatsuji Miyoshi’s poems for PIW. Jeffrey Angles’ translations are marked by an asterisk after the title.

Bibliography

Poetry

Sokuryo-sen (Surveyor Ship), Daiichi-shobo, 1930

Nanso-shu (Poems from the South Window), Shii no ki sha, 1932

Kanka-shu (Poems in the Quiet), Shikisha, 1934

Sanka-shu (Mountain Fruits), Shikisha, 1935

Tsuchikemuri (Dust Devil), Sogensha, Tokyo, 1939

Kusasenri (Grassy Crater Basin), Shikisha, 1939

Ittensho (Striking One O’clock), Sogensha, Tokyo, 1941

Sho mukuitaru (Victorious News Arrives), Style sha, 1942

Kiryo totose (A Decade of Journey), Usui shobo, 1942

Asana shu (Morning Meal), Seijisha, 1943

Kantaku (Wooden Clappers in the Cold), Sogensha, Tokyo, 1944

Hanakatami (Flower Basket), Seijisha, 1943

Haru no tabibito (Spring Traveller), 1945

Kokyo no hana (Flowers from Home), Osaka Sogensha, Osaka, 1946

Suna no toride (Fort of Sand), Usui shobo, 1946

Nikko gekko shu (Poems of Sun Light and Moon Light), Takagiri shoin, 1947

Rakuda no kobu ni matagatte (Straddling the Camel’s Hump), Sogensha, Tokyo, 1952

Teihon Miyoshi Tatsuji sishu (Authorized Edition: Complete Poems of Tatsuji Miyoshi), Chikuma shobo, Tokyo, 1962

Tanka collection

Himawari (Sun Flower), Shii no ki sha, 1934

Prose

Shi o yomu hito no tame ni (For You Who Read Poems: a Guidebook), Shibundo, 1952

Haiku Kansho (How to Appreciate Haiku), Chikuma Shobo, Tokyo, 1955

Hagiwara Sakutaro, Chikuma Shobo, Tokyo, 1963