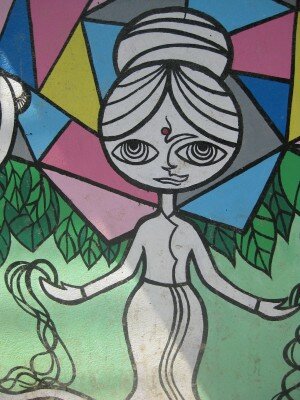

Sovereign woman

When a voice of assured affirmation anchors itself in an act of violation and violence as victim, the words ‘transformation’ and ‘overcoming’ can only approximate the writer’s intention. In the poem ‘Wound’, Banira Giri does more than raise a voice against rape and the personal wound the victim bears, she transforms through the powers of language and the inner strength of adversity overcome, the stigmata of violation into an emblem of power. ‘Wound’ – already the softening occurs, the doubling of the act, the vowels, not the disavowal, the ‘V’ for violation, like a flag waving in the wind, like something touched not with one lip but two.

For Giri and for the culture she seeks to reclaim in her poetry, a crime more consequential than violation is abandonment. Within her writing the ideal of wholeness, of man and woman complementing and completing, of world and beings sustaining and surpassing, is seen as a given within nature and when seen well, when understood, is taken up and affirmed in human creation and in culture. In ‘Pashugayatri’ she portrays the cultural loss when the task of sustaining has been abandoned.

completely helpless, bereft and naked,

pitiful Bagmati . . . stagnant within

. . . only scars of memory . . .

the rush of her waters, an encrusted scab

. . . through the dry banks of her chest

(she) whispers the Pashugayatri mantra..

and she is shocked

"Ay ai, Men are men after all,

though they throw a flood of filth into the Bagmati,

though they make the Bagmati a River-Of-Sand

. . . who is she to have them listen. . . ?"

She herself feels ashamed, troubled, sobs

In preparation to enter the underworld for ever,

seen by no one, for the last time,

stops for a moment during the still of night,

tries to wash the feet of Lord Pashupati, but cannot

Bagmati, of only a thin line, only a name,

breathless, weak, waterless, Bagmati

disheartened while trying to bid farewell to Pashupati

the whips of sand

chase her

the whips of sand

drive her out

Where man appropriates, woman creates; where creation itself is violated, what use is poetry? In ‘Kathmandu’ contemporary history takes on the pretensions of literature, but without an inner dynamic. Lack repeats itself, what seduces traps and the refrains of culture dead end. Not only is poetry without use, history itself is useless.

is an epic . . .

. . . forever repeating the same laments

In ‘Each One a Despot Jung’ Bahadur Giri finds the citizen-to-be at the nexus of a stalemate where culture and history have yet to decide their fate. More displaced than settled, without public stance, each person, lacking definition, sensing but not knowing the what to be or the who they are, turns inward where wealth of images impressed upon the eye are lacking in substance, fleeting, and gone – only to deepen their striving, their unrealized claims.

with a comet in the sky

with a waterfall about to drop in panic

from a mountainside

with a bus conductor bloodied

by a rush of crowds while opening a door

Conviction keeps changing form

each moment—

Within this inward dynamic is a wariness that parallels the tentativeness of events. One is ever on the verge of action, but the what and how of changing possibility and the threat of violence can neither cohere nor stop the drift apart from the identity-less crowd. In aimless anomie nurtured by nostalgia, memory neither holds nor shapes affirmation. Left to grasp at what it can, the self – until and only if it can void the threat it feels in a coup of the self, in a victory of its solitary affirmation – lives in suppressed fear, in prophetic panic, in a state of self-imposed tyranny.

In ‘Time You Are Always a Winner’ Giri graphs the trope of her concern within a more human helplessness. Time has sovereignty over the human realm: a rule against which there is no resistance other than the recognition of its power. Here, as in ‘Wound’, the poetess takes on the force of the victor, identifying herself with its impress almost as a challenge a dare

swooping down on a chicken

wash me away

like a flood destroying the fields,

and, like my daughter sweeping out dirt,

sweep me from the threshold

with a single stroke,

sweep me from the threshold with a single stroke.

Concurrent with the belief that poetry can create a world and affirm a self, Banira Giri’s poems stand as witness, warning and celebration, not to be read as a personal history of triumph over life, but as ongoing encounter: the cry ‘Violation’ can still be heard, “the whips of sand” still drive the goddess out, bodies are still branded, wives still beaten, but the epic can no longer repeat the same laments, and no living man nor woman shall, with human acquiescence, feed the night with alibis. Banira Giri’s poems testify in her culture and society to that which can no longer be as it was.