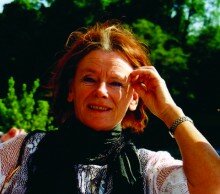

Gro Dahle made her debut with the poetry collection Audiens (Audience) in 1987, and since then she has been one of Norway’s most influential poets. Apart from several poetry collections, she has written novels, short stories, radio plays, essays and children’s books. The last genre has become an increasingly larger part of Dahle’s literary pursuits in the later years.

Her three first collections, Audiens (1987), Apens evangelium (The Ape’s Gospel, 1989) and Linnea-pasjonen (The Linnea Passion, 1992) all build up a gallery of characters within a mythological world, with a collection of components that is constantly repeated. The poet explores central myths in Western culture, including Norse and Christian concepts. At the same time, she paints more modern and scientific world pictures and interprets these afresh within her own mythical contexts.

This first phase of Dahle’s lyrical authorship is often characterised as falling within Naivisme. Defined as a child-like stylised universe, often from a low perspective as if from a child’s point of view, the concept may well be apt. A hallmark of her poems is precisely the way they ridicule human vanity, and the utter seriousness and devotion which are often connected with the concept ’lyricism’. To this purpose, the poet always uses the child as her ally, without this child in any way seeming to be an infantile splitting of the ‘I’ itself: the child is just there and combines with the adult person’s way of thinking, seeing and expressing himself or herself.

The impulse of Concretism in European poetry shows itself in more than one way in Gro Dahle’s poetical language, and in this context we can mention writers such as the American William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) and the Norwegians Jan Erik Vold (1939-) and Olav H. Hauge (1908-1994) as likely role models. The emphasis on the integral value of things as things reinforces the impression of a kinship with these poets.

The collection Regnværsgåter (Riddles in Rainy Weather, 1994) marks a shift in Dahle’s manner of writing. It is possible that the poems are inspired by the Zen-Buddist Kōan tradition, for the poems have, as the title suggests, that special character of being riddles where the division between question and answer is erased. In Kōan neither question nor answer has a rational meaning, rather these categories are meant to be conquered through intuition and meditation. It is possible to read the poems in Regnværsgåter as just such a constantly on-going ‘Kōan’ exercise (two of the poems from Regnværsgåter are included in Poetry International’s selection).

The impulse of Naivisme is, as always in Dahle, the driving force; the ingenuous mode of address, the wondering and the oblique optics. The poems may be reminiscent of children’s verse, and that is what is so strange: that you constantly have to ask yourself to whom these poems are directed. It is as if they aim at someone who exists far inside you. Yes, it may sound like a cliché, but I still believe it is appropriate to say that her poems speak to a child that the adult and literary educated reader often has problems acknowledging. In that sense, the address in itself may be perceived as a provocation.