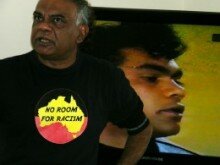

Lionel Fogarty is one of the best known contemporary Aboriginal Australian writers. For some thirty years, he has been excavating a space in which his community and culture is recuperated and asserted, while also subverting and destabilising dominant discourses, both political and poetic. A Yugambeh man, Fogarty was born on Wakka Wakka land in South Western Queensland near Murgon on a ‘punishment reserve’ outside Cherbourg. Throughout the 1970s, he worked as an activist for Aboriginal Land Rights and protesting Aboriginal deaths in custody. In 1993, his younger brother, Daniel Yock, died while in police custody. He has published numerous collections of poetry in Australia through small presses and major publishing houses. His most recent collections include Mogwie Idan: Stories of the land, (Vagabond Press, 2012) and Eelahroo (Long Ago) Nyah (Looking) Möbö-Möbö (Future) (Vagabond Press, 2014).

As well as being integral to any reading of contemporary Australian literature, Fogarty’s work fulfils any number of positions within traditional literary and cultural determinations – as postcolonial literature, protest literature, black writing, contemporary surrealism. Drawn from Fogarty’s seemingly inexhaustible reserves of imagination, linguistic innovation and experimentation and deep political conscience and drive, his poetry is a powerful transcultural force. It is righteous and revolutionary in its anger over the crimes and injustices perpetrated by White Australia on Australian Aborigines. Fogarty also attacks contemporary Australian poetics with a fierce spirit, recasting language as a weapon and a tool as he writes across and transforms Bandjalang, Aboriginal English, and Australian English, in ways that leave much contemporary experimental poetry seeming effete and pretentious.

Prominent Indigenous Australian novelist, academic and social commentator Anita Heiss recently wrote, “Lionel Fogarty’s work as a guerrilla poet has been known to me for over two decades, but he released his first collection of poetry – Kargun – in 1980. Lionel has continued to write with powerful passion about issues close to the heart of most Indigenous people: injustice, land rights, identity, language, black deaths in custody and the ongoing consequences of colonisation. Lionel’s writing focuses on our need to face a future without oppression and he demonstrates a desire to pass on his own knowledge and experience through the written word.”

Sabina Hopfer has commented that Fogarty’s poems are, however, “rarely either of a solely political or spiritual nature. Most of them combine both elements”. More importantly with regard to usage, Hopfer notes: “The reality of orality constantly challenges and transforms the reality of literacy. Fogarty’s aim being to reconcile the two.” It is this aim of reconciliation that makes Fogarty’s work particularly challenging to conceptions of English (be it Aboriginal English, Australian English or Standard English) and its cultural context – and potentially liberating for colonised and coloniser alike: the complex hybridisation in Fogarty’s work is an invitation to cross-cultural understanding that challenges both writer and reader to pursue greater understanding of themselves and their relationship with each other within a shared linguistic community.

The challenge is bi-directional as it demands of the poem’s speaker an equal commitment to self-understanding and communication, reconciling dichotomies of usage and identity (oral/literate, spiritual/political, indigenous/non-indigenous, past/present, self/other) into a shared experience and language community focused in the poem. As an act of reconciliation arguably demands, Fogarty’s poems asks both reader and speaker to give to the other, and, in the process, produce an example of a community able to exist and function from plural centres. Fogarty’s use and development of Aboriginal English in terms of postcolonial literature represents not simply an effort at cultural maintenance and recuperation, but also its inscription on equal terms with national and international literatures. As such, his work can be seen not simply as a counterdiscourse but as an integrated, less dialectically defined, reconception of English – literature and usage – wherein a reciprocal biculturalisation is demanded of the colonisers.

The complexity of Fogarty’s poetry lies both in its cultural and linguistic resources. Fogarty’s poetry demands readers to engage with and consider broader areas of Aboriginal and coloniser history. Combining a brutally direct gaze and statement with allusion and elision, Fogarty forces readers who accept the challenges of his work to fill the gaps in their knowledge with regard to Aboriginal history and culture, while refiguring their position in an utterly changed symbolic landscape. Fogarty notes:

What I try to do in my writings is to show that no matter what English you get, English is the most bastardised language in the world – but it’s not all bad – it does not give any natural flavour to what Aboriginal language is about. At the same time I try to show them that Aboriginal language is a natural language, is a god-given language, a very spiritual language.

This relationship that Fogarty is consciously developing between English and Aboriginal languages represents at one level a postcolonial re-inscription of English into the power flows that it has disrupted and in many cases heinously destroyed, and at another level, presents an active and participatory reconception of English as stemming from plural sources and not reduceable to normative linguistic or cultural constructions. Fogarty’s work protests the various injustices perpetrated on Aboriginal populations over the course of Australia’s colonial/postcolonial history, and demands understanding and justice be reached that is not dictated by the dominant discourse nor in its bastardised terms. Confronting and relentless in its pursuit of understanding and justice on its own terms, Fogarty's work opens up new paths towards these ends. Fogarty noted:

The way I see my books going . . . is creating a collective thought within people so they they can go back and read other Aboriginal literature or whiteman’s literature, either historical or present-day, or when they read things like deaths in custody, this will help them to meditate, so that they can create an energy, good energy.

Fogarty’s poetry becomes a site in which colonisation and dispossession are played out, destabilising the invading tradition and colonising language that wrought havoc on indigenous culture, languages and identity. Fogarty’s work demands the reader attend both to the culture recuperated and the language in which this recuperation occurs. Having read Fogarty’s work, it is impossible to view Australian poetry in the same way again without thereby being complicit in the alienation and dispossession that the work protests against. This is poetry to read and re-read, to attend and open to and so be changed by, in painful, uncomfortable and harrowing ways, and so come closer to an understanding of the still living history of Australian injustice and dispossession.

Bibliography

Poetry

Yoogum Yoogum, Ringwood Vic., Penguin, 1982

Ngutji, with illustrations by Lyn Briggs. Spring Hill QLD, Murrie Coo-ee, 1984

New and Selected Poems, Munaldjali, Mutuerjaraera. Melbourne, Hyland House, 1995

Minyung Woolah Binnung: What Saying Says, Southport QLD, Keeaira Press, 2004

Connection Requital, Sydney, Vagabond Press, 2010

Mogwie Idan: Stories of the Land , Vagabond Press, 2012

Eelahroo (Long Ago) Nyah (Looking) Möbö-Möbö (Future), Vagabond Press, 2014

Links

Home is where the heart is: panel discussion featuring Lionel Fogarty at Darwin's Wordstorm festival

Fiona Hile Reviews Lionel Fogarty in Cordite Poetry Magazine

Tim Wright reviews Mogwie-Idan Stories of the Land by Lionel Fogarty in Mascara Magazine

Donna Ward, The Poetic Politics of Lionel Fogarty, published on Australian Poetry

Three poems published in Jacket

Interview with Philip Mead in Jacket

Several poems published on the Red Room Company’s website