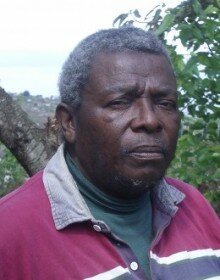

Mafika Pascal Gwala was born on 5 October 1946 in Verulam, outside Durban. The second of five children, his mother was a domestic worker and his father was a labourer on the railways. Gwala matriculated from Inkamana High, a Benedictine mission school in Vryheid, KwaZulu-Natal. He held various positions, including factory worker, legal clerk, secondary school teacher and industrial relations officer. Although he initially sacrificed his studies in order to serve the Black Consciousness Movement, Gwala went on to complete an M Phil at the University of Natal, studying the politics of development in Third World countries. At the University of Manchester he extended his research into the field of adult education.

Writing in English and Zulu, Gwala’s first attempts at poetry started in his twenties. A short story first appeared in Classic, followed by poems in Ophir. His contribution as a socio-cultural critic, essayist, editor and poet, has significantly influenced a generation of South African writers and thinkers. He edited Black Review in 1973 and his poems, short stories and essays appeared in various journals and anthologies, locally and internationally. While not as prolific as some of his contemporaries, Gwala is one of the most under-recognised and undervalued South African poets.

Gwala, who once said, “You cannot divorce language from power,” had a sensibility deeply rooted in the Black Consciousness movement. Along with his friend and comrade, Steve Biko, he was a member of the black South African Student Organisation and the Black Communities Project in Durban, which was banned in 1977.

“We didn’t take Black Consciousness as a kind of Bible, it was just a trend . . . a necessary one because it meant bringing in what the white opposition couldn’t bring into the struggle.”

Arrested at the same time as Biko, Gwala spent six months in detention. This was the year his first volume of poetry, Jol'iinkomo, was published and co-incidentally, the year that the groundbreaking journal Staffrider was launched and immediately banned.

Jol'iinkomo, which translates as ‘Bringing the cattle home to the kraal’, was originally a song popularised by the jazz diva, Miriam Makeba. In the opening poem of the collection, Gwala writes: “I should bring some lines home/ to the kraal of my Black experience.”

No More Lullabies (1982) explores a changing political sensibility, as Gwala moved toward a more non-racial socialism and a less militant aesthetic. Musho! Zulu Popular Praises (1991), an editorial collaboration with Liz Gunner, is a seminal text providing a literary commentary on Zulu poetry. It includes two of his praise poems.

Along with poets like Oswald Mtshali, Mongane Wally Serote, James Matthews, Njabulo Ndebele and Sipho Sepamla, who expressed the aspirations of Black Consciousness and articulated the call to struggle and resistance, Gwala is often labelled as one of the so-called ‘Soweto Poets’. This was a term he rejected outright as the poets typically bracketed in the group came from all around the country.

Theirs was the poetry of resistance, the rally cry at mass meetings and underground gatherings and, all too often, funerals. His was a poetry full of verve and passion, steeped in the lilt and sway of the music that mirrored the torque and stretch as he reinvented language.

Music features in much of his poetry: ‘Children of Nonti’ gives voice to the songs of Black voices and even the kettle sings in ‘One Small Boy Longs for Summer’; and the musicians who inspired him appear throughout his works. In ‘Jol'iinkomo’, the title poem of his collection, Miriam Makeba rightly makes an appearance; in ‘Night Party’ he calls to Charlie Parker and Jimi Hendrix; ‘Bonk’abajahile’ refers to the South African jazzman, Philip Tabane; and ‘Getting Off the Ride’ climaxes in a howl of ecstatic grief mirroring Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme’.

A founder member of the Mpumalanga Arts Ensemble based in Hammarsdale, Gwala’s soul was fed and watered by this group of comrades – musicians, artists and writers – which included the poets Nkathazo ka Mnyayiza and Ben Dikobe Martins. The group was integral to the establishment of a viable working-class arts movement in the region. In particular, it provided the impetus for the magazine Staffrider, which arose out of discussions with Mike Kirkwood.

Ari Sitas, describing Gwala’s published oeuvre, says that he “exhausted the creative limits of the scripted word here: beyond his poetry lies an unknown, an untested terrain, for every subsequent poet in Natal has been consciously or unconsciously writing in his shadow. From the gutsy exuberance of the first work, to the tortured lines of the second, to finally the authority of line, rhythm and sound of the third, we are faced with a complex inheritance.”

Sitas points to the influence of Mazisi Kunene: “Jol'iinkomo is a distorted echo of Kunene’s call; it is distorted and ‘polluted’ by the shack worlds of Mpumalanga and the grit of Durban and it is written in English with the rhythms and lexis of Zulu pressing heavily on it.”

He refers to other pressures that make Gwala’s a very different English, acknowledging a conscious mangling of everyday speech’s rhythms and localisms. “Still Kunene’s echo is there, fanned further by the rising tides of the black consciousness movement in South Africa, in which Gwala had a formative yet peculiar role to play.”

‘'The Children of Nonti’ was written in a morning at the urging of Strini Moodley, founder of the first union of Black theatre. Sitas describes it as “an Africanist affirmation of pride and dignity with few equivalents in the Seventies; but it is a black consciousness soaked in working class grit.”

In the onomatopoeically titled ‘Gumba, Gumba, Gumba’, the rhythm of the beatbox is the steady accompaniment for the poet’s complaint. He does not shy from criticising his fellows who undermine the social fabric of the community right along with the venal agents of the state.

Gwala’s legacy lives on in the contemporary work of the next generation of writers, men who were inspired by his example, encouragement and guidance: Fred Khumalo, Mandla Langa, Sandile Ngidi, Chris van Wyk and Ndumiso Ngcobo.

Bibliography

Poetry

Jol'iinkomo, Johannesburg, AD Donker, 1977

No More Lullabies, Johannesburg, Ravan, 1982

Compilations

Black Review, Durban, Black Community Programmes, 1973

Musho! Zulu Popular Praises (with Liz Gunner) Michigan State University, 1991

Awards

2007: The SALA Literary Lifetime Award

Links

A poem on the SA History website

Andrea Meeson interviews Mafika Gwala on Chimurenga

A poem on the Poetry Africa website

An extract from 'Getting Off the Ride' on the KZN Literary Tourism website

Mphutlane Wa Bofelo comments on Mafika Gwala in his essay on contemporary South African slam poetry in Pambazuka News

Michael Chapman's essay on the Soweto Poets refers to and set the context for Mafika Gwala's oeuvre.

Further reading

Michael Chapman, Soweto Poetry: Literary Perspectives, Johannesburg, McGraw-Hill, 1982

Colin Gardner, 'Catharsis: From Aristotle to Mafika Gwala.' Theoria: A Journal of Studies in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 64 (1985): 29-41

Mafika Gwala, 'Writing as a Cultural Weapon' from Momentum, Margaret Daymond, Johan Jacobs, and Margaret Lenta (eds.). University of Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, 1985. 37-53.

Peter Horn, Writing my Reading: Essays on Literary Politics in South Africa, Amsterdam, Rodopi Press (1994)

Thengamehlo Ngewenya, 'Towards a National Culture', Staffrider 8, 1989

John Povey, 'The Poetry of Mafika Gwala', Commonwealth Essays and Studies 8, no.2 1986, p84-93

Ari Sitas, 'Traditions of Poetry in Natal', Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1990)

Michael Chapman, Soweto Poetry: Literary Perspectives, Johannesburg, McGraw-Hill, 1982

Colin Gardner, ‘Catharsis: From Aristotle to Mafika Gwala’, Theoria: A Journal of Studies in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences,Vol. 64, 1985

Mafika Gwala, ‘Writing as a Cultural Weapon’ from Momentum, Margaret Daymond, Johan Jacobs, and Margaret Lenta (eds.), Pietermaritzburg, University of Natal Press, 1985

Peter Horn, Writing my Reading: Essays on Literary Politics in South Africa, Amsterdam, Rodopi Press, 1994

Thengamehlo Ngewenya, ‘Towards a National Culture’, Staffrider, Vol. 8, 1989

John Povey, ‘The Poetry of Mafika Gwala’, Commonwealth Essays and Studies Vol. 8, No.2, 1986

Ari Sitas, ‘Traditions of Poetry in Natal’, Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1990