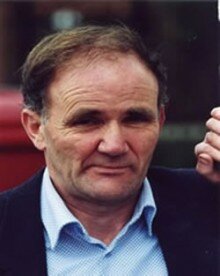

Eugene O’Connell was born near Kiskeam in northwest Cork in 1951. He has published a number of chapbooks, one full collection of poems, One Clear Call (Bradshaw Books, 2003), and one book of translations, Flying Blind (Southword Editions), which was volume 12 of the Cork European City of Culture Translation Series. Diviner, a new collection of his poems, was published by Three Spires Press in 2009. He is editor of The Cork Literary Review. A volume of memoirs is forthcoming in 2010.

Eugene O’Connell was born in 1951 and raised in the hill country of Kiskeam in northwest Cork. He went to the national school and spent one painful year at a boarding school in Cork, but then came back to a secondary school at Boherbue. He trained for two years, between 1969 and 1971, at St Patrick’s Teacher Training College in Dublin to qualify as a primary-school teacher, enjoyed the work, read avidly, and rummaged through book barrows and second-hand bookshops along the quays. He developed a particular interest in modern drama, in Joe Orton and Alan Ayckbourn.

At the age of nineteen he began teaching at St Patrick’s National School on Gardiner’s Hill in Cork, where Daniel Corkery had been principal and Frank O’Connor and Seamus Murphy had been pupils. He was stimulated by the presence in Cork of the poets Paul Durcan, Sean Dunne and Thomas McCarthy. At NUI Cork, which he attended from 1974 to 1979, he had Sean Lucy and John Montague as instructors. He was awarded a BA and a Higher Diploma in Education.

In a sense he never left the hills, farms and people of his native place. Much like Patrick Kavanagh who went back to the stony grey soil of Monaghan to feed his imagination, O’Connell’s writing has been nourished by a sense of home. His earlier poems incorporate Irish words like súil, meaning an opening in a ditch, and driongán, meaning a thin, sickly person. His poems have a consistency of language and focus in which a specific and recognisable world accumulates.

Behind the plain speech is a reflective intelligence that recalls ordinary people and events. His modest manner is accompanied by a shrewd intelligence and a technique attuned to the poet’s sensibility. He is not given to exaggeration. Instead, he prefers to record through exact delineation, disguising pain, loss and compassion behind an ironical approach. If he tries to identify the source of his technique of understatement he refers to W.B. Yeats’s trust in the half-said. In fact, an oblique way of speaking was a natural part of the culture in which he was raised. He is a realist with a sense of humour that emerges in broad strokes, with sharp wit and scorn for human foolishness. While there are references to Irish and classical mythology, and intimations of the other world, the poet’s eyes are focused on the everyday and the familiar. He sees reality but understands the ghostly otherworld that impinges on people’s lives. For O’Connell the spiritual and the artistic are one.

While he is drawn back to what he remembers, he handles the material of memories with restraint, and this reserve characterises his two main collections – One Clear Call, 2003, and Diviner, 2009, the former published by Bradshaw Books, the latter by Three Spires Press, both in Cork. While they may focus on people who live on the margin, remote from towns, and a way of life that is rural and traditional, these two collections establish O’Connell as a particular kind of poet, with his own style and idiom. He has an affinity with William Wordsworth’s ideal of communion with nature. With that affinity goes a dislike of ivory towers and pomposity.

When he reflects on what he does, he understands that the rural serves as focus for his view of the world. The pastoral reflects how he feels and what he thinks about human existence. Fundamentally, he is interested in human and cultural relationships, in the search for love, and more recently he feels a yearning for spiritual well-being, a means of linking the physical and the spiritual.

There is a gradual shift in his work from the outer to the inner world. What seems distanced and rural is in fact connected with contemporary life, with the isolation of modern man. What is observed in the countryside parallels what he finds in cities and towns. The recent emergence of a dark, comic, even surreal quality in the poems enables him to present the tragic and the comic as two sides of the one coin. Reflecting seriously on what he does, O’Connell has developed a style and technique that express how he feels and thinks.

Selected Bibliography

Poetry

One Clear Call, Bradshaw Books, Cork, 2003

Diviner, Three Spires Press, Cork, 2009

Poetry Translation

Flying Blind from the Latvian of Guntars Godins, Southword Editions, 2005

Links

Link to information about Flying Blind

Review of Diviner